Case Study: University of Delaware Agrisolar Research

As we strive for climate change solutions, competition over land for food production or clean energy production is an emerging challenge to address this challenge, demonstrations of systems that produce energy and food on the same land are needed to usher in solution-scale adoption of these practices. A new research project at the University of Delaware (UD) will study the results of growing food crops underneath uniquely designed PV solar arrays. SolAgra Corporation will oversee the installation of two solar arrays at the UD Newark and Georgetown campuses. Once built, these sites will have the potential to demonstrate just how symbiotic solar energy and agricultural production can be.

Professors Steven Hegedus, UD Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Gordon Johnson of the Plant and Soil Sciences Department, and Emmalea Ernest, Agriculture Program Leader, will work with their students to investigate the potential benefits to food crops grown beneath the PV arrays. All the preliminary engineering studies for the project are completed and approved, and construction is on track to be completed by the start of the growing season in April 2024. UD will fund the installation of the solar arrays and the initial crop plantings underneath. Further funding from the US Department of Agriculture and the US Department of Energy is being pursued to sustain a multiyear study of the sites.

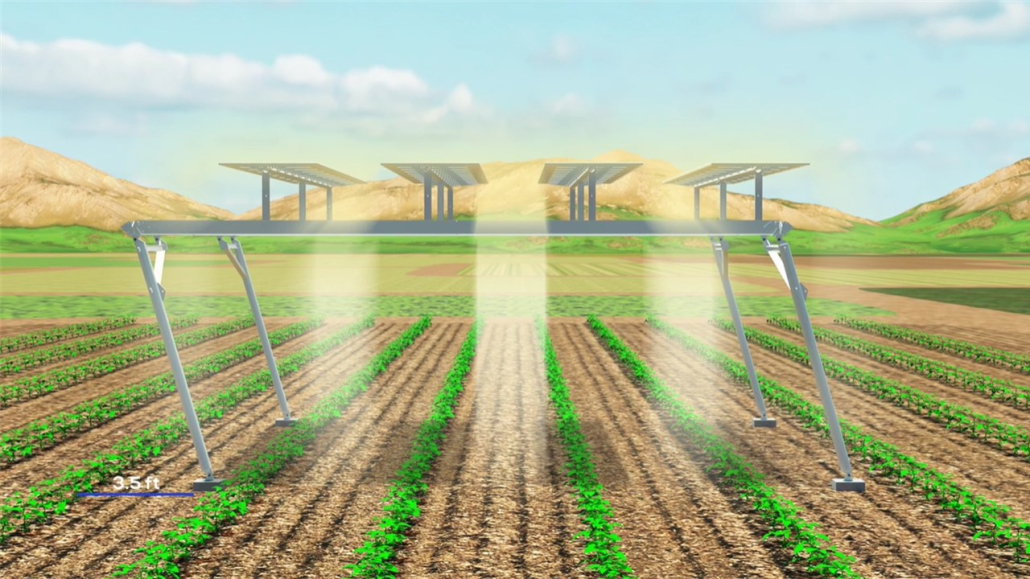

Barry Sgarrella, founder and CEO of SolAgra, said he developed the raised solar platform that will be used in the UD project to “help farm families be more profitable and to slow the trend of farmland being consumed by commercial development.” The SolAgra Farming Array™ will consist of elevated array segments with 15.5 feet of clearance to accommodate the tallest agricultural equipment. The racking will be assembled and the solar panels installed at ground level and then hinged into an upright position.

The panels will track the sun to increase energy production by as much as 15% and, when needed, they can be rotated so the panel edge is perpendicular to the sun to allow the maximum amount of sunlight to hit the crops below, a function Sgarrella calls CounterTracking™. This, coupled with the unique ability to shift the entire array east or west, called DynamicShifting™, will deliver varying degrees of sunlight or shade to crops planted below as needed. The rows of solar modules will be installed on 11.25-foot centers, a relatively dense panel row spacing for agrisolar cropping applications.

Dynamic Shifting allows the entire array to move side to side for the least amount of shading possible.

Each array segment will be 35 by 45 feet and is designed to hold enough solar panels to produce 17 kW of electricity. The array segments will be modular and can be scaled up to much larger size arrays. Each research site at the UD project will contain two array segments totaling 68 kW of installed solar panels. The two systems will be identical except that the array installed on the Newark campus will house bifacial solar panels to study how much electric production can be gained from light reflecting off the crops and ground back to the underside of the panels. Sgarrella stated that the cost to install a segment is comparable to other raised-platform solar arrays of the same size, and costs would decrease for larger installations as economy of scale is achieved.

According to Professor Hegedus, part of the research will involve looking at crop production at different shading levels. Photo saturation is the point at which plants cannot efficiently utilize more sunlight in the photosynthesis process and once the crops are at that point, it makes sense to utilize the light for energy production. The crops that will be included in this study are strawberries, tomatoes, peppers, and lettuce and were chosen because of their high market value. The flexibility of the SolAgra Farming Array™ design will allow the researchers, through controls on their smart phone or tablet, to provide full sun, full shade, or anything in between based on individual crop needs. The results can then be used to help develop shading schedule algorithms that can control the system for different crops.

Sensors will be used to measure direct and diffuse illumination under the panels, soil and air temperatures, humidity, and crop temperatures to start quantifying crop benefits. It’s expected that the soil in the shade of the panels will retain moisture and that the crops will require less irrigation, which has been shown as a benefit of agrivoltaic cropping systems in other research.

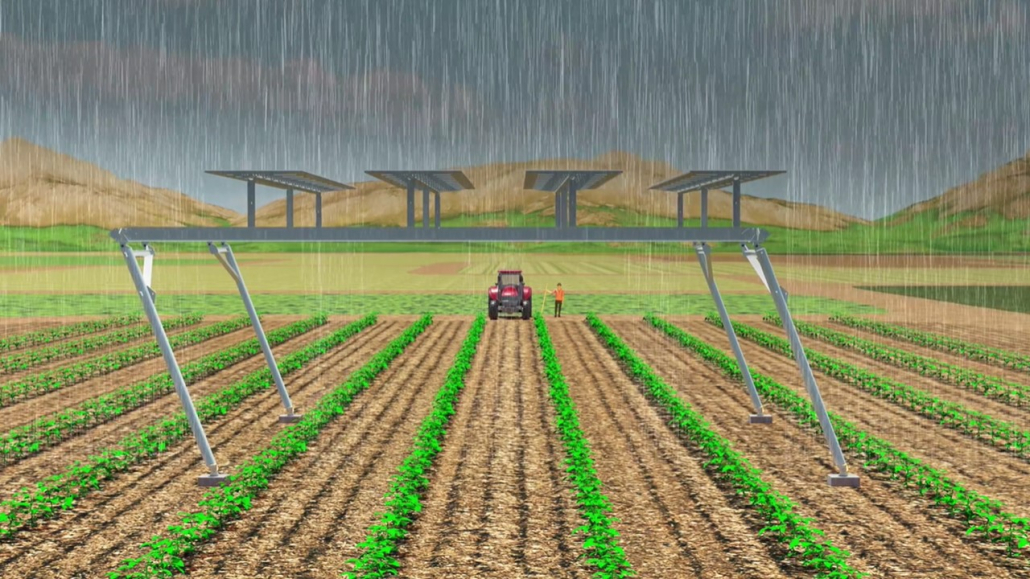

The researchers will also orient the panels horizontally to test the system’s ability to protect crops from severe weather like rain or hale. Even in this horizontal “umbrella” position, the panels will be able to produce 80% of their rated power. The benefits of protecting crops from damaging hail and heavy rain are evident, but many crops could benefit from the protection and shade control this system could offer. For example, this system could protect against sunscald, which can affect most crops in the right conditions and render them unmarketable. And, if grape growers could control sun levels, they could affect the acidity and sugar levels of the grape, which is very important in wine production. Many crops could benefit if growers could protect them with a solar panel covering, especially as weather conditions become more extreme.

An umbrella effect is created when the solar panels are placed in a horizontal position and shifted over the top of each crop row.

Professor Hegedus believes that one of the biggest indirect benefits of proving this type of agrisolar system is that opposition to large solar installations on farmland might dissipate once neighbors realize that farming is not being replaced by solar panels but rather augmenting with an additional layer of income. He said, “farming is just carbon-based solar energy so now we’re combining two different ways of harvesting that energy.”

The project’s researchers will be challenged by the quantity of data gathered from multiple sensors over a nine-month growing season at two locations. Advanced data analytic techniques will be necessary to organize and effectively interpret all the information. Future work will utilize the results from the study to form shading schedules that are tuned to each geographic and climate region to accommodate sun angle changes and local weather conditions so that the technology can be effectively utilized by farmers.

In the face of climate change, well-designed agrisolar systems may give farmers a better chance to stay in business. Having the ability to protect crops and to control the shade levels could optimize production while at the same time producing revenue from solar power production, keeping farmland in production and profitable. Applications of this technology will be studied at UD in the coming years over the course of this project.

Photos courtesy of Solagra.