Gary Paul Nabhan, PhD., Agroecologist, Borderlands Restoration Network

When most Americans think of crop production, they tend to imagine crops growing in full sunlight to achieve their full potential for productivity. But over decades,there has always been crop production in shade habitats or constructed environments, as well. Indeed, much of the coffee and chocolate (cocoa) consumed as beverages has been grown under shade-bearing, nitrogen-fixing legume trees such as madrecacao (Glyericidia sepia), a tropical tree with a dense and expansive canopy that protects understory crops from excessive heat and damaging radiation.

Virtually all the food crops, forages, and medicinal herbs grown in North American agroforestry and alley-cropping systems are to some extent shade-tolerant. Many—like chile peppers—can comfortably tolerate a 35% to 50% reduction in photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) compared to open sunlight all day. They seldom suffer a yield reduction due to less sunlight in this range, especially from noon to 4 p.m. Iin fact, yields in some varieties are augmented, perhaps because a significant percentage of all arid, temperate, and tropical wild plants evolved to begin their lives under the shade of “nurse plants” and have evolved shade tolerance to varying degrees over millennia. More than 30,000 farmers in the U.S. were engaging in one or more types of agroforestry practices by 2017, when agrivoltaic practices first hit the American scene.

Agrivoltaic pepper plants in Arizona. Photo: NCAT

Benefits and Challenges of Solar and Crop Co-Location

So, what kind of benefits do shade-grown crops receive, and what are the challenges of growing crops under any kind of shade, for both the trees and the solar panels?

Benefits

Let’s first look at the benefits. Shade reduces the amount of sunburn or sun scald that understory plants receive but particularly reduces the effects of damaging ultraviolet radiation. It also serves as a temperature buffer, reducing high summer temperatures by as much as 4°F to 6°F and keeping winter temperatures in crop canopies 2°F to 4°F warmer—in some cases, enough to avert premature freezes or to extend the frost-free growing season by as much as three weeks. With less direct sun, evaporation of water from the soil and transpiration from the leaves are reduced, and soil moisture stress may not be as severe.

The flowers of crops abort less in cooler temperatures, and they also attract more pollinators. Plant desiccation is not only reduced, but the nitrogen content of the foliage also does not spike enough to trigger feeding frenzies by leaf-sucking or browsing insects. At the same time, the Brix levels—an indicator of how sweet and nutritious vegetables and herbs might be—is sustained at higher levels, adding to the value of the crop.

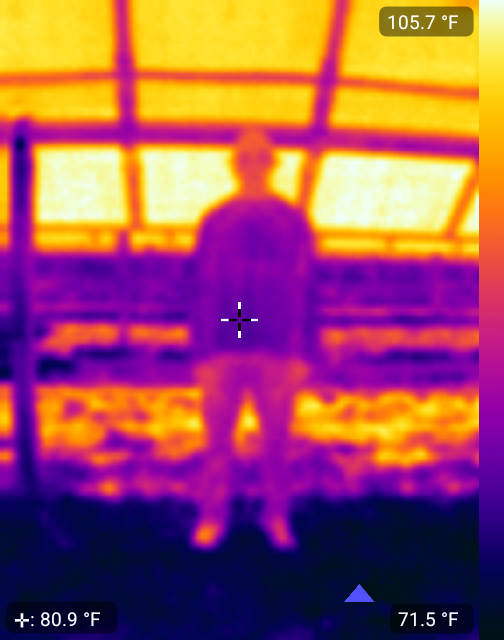

Perhaps the ultimate advantage is that it buffers farmworkers managing or harvesting from severe heat stress and dehydration in hot summers, improving their harvesting efficiency and reducing their vulnerability to hazards and illness. In 2023 alone, 30,000 more outdoor workers in the U.S. succumbed to heat stress than in any other year in recorded history. Since hand-harvested crops are time-consuming, their harvesters are especially vulnerable.

Thermal image showing farm worker under a solar panel with a body temperature of 80°F and an outdoor temperature over 100°F. Photo: NCAT

Challenges

The disadvantages of co-location are more obvious for some sun-loving plants than for others. If the canopy tree or solar panel “competes” for too much light, it will result in reductions in photosynthesis and yields, thereby impeding the growth of the underling. However, there may be more humidity retained in the under-panel microclimate that fosters fungal diseases and possibly leads to more plant damage from insects that thrive on the fungal environment.

Crop height may be impeded, requiring more pruning or difficulty in harvesting. And of course, most mechanical harvesters of high stature are eliminated from use if panel are 5 meters (16.4 feet) or less in height.

Lastly, the space under photovoltaic panels is economically and ecologically costly per square meter; the metal, copper wiring and glass or plastic fiber glazing in photovoltaic panels is burdened with considerable “embedded energy” within it, so each panel provides small but very expensive growing space (except when compared to high-tech, computerized greenhouses with air conditioning and movable benches.) It is unlikely that growing grains or dry beans under photovoltaic arrays will ever be cost-effective.

So, what is different and distinctive about the shaded growing spaces under photovoltaic panels? For one thing, these areas have solid or slotted covers, rather than being diffused and porous like most leafy canopies. Secondly, all constructed spaces in a photovoltaic array are of similar height and size, whereas the height and size(s) are highly variable in natural or semi-managed forests.

In natural settings, “nurse trees” also offer much more than shade and temperature buffering to understory plants; they also offer mycorrhizal connections and soil fertility renewal. Some deep-rooted legume trees also pump and leak water and nutrients to other plants in their nurse plant guild that are too young to do this on their own

The crops discussed here that are most suitable for agrivoltaics conditions are high-value cash crops or nutritionally dense fruits and vegetables for home or community consumption. These crops are more suitable for agrivoltaics conditions compared to grain or bean crops, for example. Medicinals and pharmafood crops would likely be a better fit for growing conditions that are produced from dual-use land environments.

Agrivoltaic pepper plants in Arizona. Photo: AgriSolar Clearinghouse

Considerations for Crop Selection

It is important to consider what shape, size, and habit of crop plants might be most appropriate for agrivoltaics production over an extended period of time. When considering crops that will be well-suited for the conditions of an agrivoltaics site, it is important to consider the following points.

Crop Characteristics:

- Vining or “bush” growth forms

- Sun-loving or shade-loving

- Height and width of fully grown plant

- Multiple harvests or single harvests required?

- Root depth

If we were to design an “ideotype” best suited to the photovoltaic micro-environment, it would need to meet at least five of the following plant characteristics:

- Vertically-vining or “indeterminate” growth forms that make maximum use of the space under solar panels by being trellised or “stiffer” scandent plants that lean upon a trellis (such as dragon fruit and capers). Vining plants that spread out beyond the perimeters of the panels may have a cooling effect that increases photovoltaic energy production efficiency (his strategy assumes that the interspaces between panels are not being utilized in another way).

- Tolerate moderate (especially mid-day) shade, with interception or screening of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in the range from 35 to 50% of total daylight,

- Growth habit that will allow for harvesting of seed, fruit, flowers, floral buds, or leaves from waist high (1 meter or 3.28 feet) to shoulder-high (1.4 to 1.8 meters or 4.59 to 5.9 feet) above the ground to allow work by hand or mechanical harvesters.

- Can be harvested or “cut” multiple times per season, pruning them to stimulate subsequent regrowth and recutting within three to four weeks of the previous harvest.

- Be either deep-rooted or shallow-rhizomatous perennials with runners, or longer-lived seasonal annuals that can be uprooted after the last harvest to allow new transplants to go into the same space.

Now that we’ve established the ideal architectural and behavioral criteria for selecting crop plants, here is a list of crops that meet three or more of these criteria. These lists emphasize high-value crop plants that have other adaptations to hot, dry conditions but may require partial shade or frequent cutting and harvesting.

Berry vines and bushes with long, arching shoots that can be both vertically and horizontally trellised: currants, dewberries, gooseberries (Ribes spp.); brambleberries, blackberries, dewberries, and loganberries (Ribes spp.), grapes, including muscadines, musquats, scuppernongs, etc. (Vitis spp.)

Arborescent and scandent cacti with high-value fruit: cochineal nopal (Opuntia cochiillifera) dragonfruit cacti, including white-fleshed pitahaya (Selinicereus undulatus), red-fleshed pitahaya (Selenicereus costaricensis), and yellow pitahaya (Selenicereus megalanthus); pitahaya agrias (Stenocereus gummosus, S. quereteroensis, and S. griseus), longer-lived seasonal annuals that can be pulled up after the last harvest to allow new transplants to go into the same space.

Short-stature shrubs with copious production of fruits, buds, or berries over a long season: capers (Capparis spinosa); capulín sand cherries (Prunus salicifolia); chiltepín, chile del arbol, shishito, etc. (Capsicum annuum); Mexican hawthorn or tejocote (Crataegus mexicana); elderberry (Sambucus nigra); goji or wolfberry (Lycium barbarum, L. chinense, L. fremontii, and L. pallidum); Persian lime (Citrus x latifolia); key lime (Citrus aurantifolia); kumquat (Fortunella margarita and hybrids); jujube (Zizyphus jujba); guava (Psidium guajava); hibiscus or Jamaican sorrel (Hibiscus sabdardiff); or maypops and passion fruit (Passiflora spp.).

Perennial culinary herbs that can tolerate (or increase production with) frequent, severe cuttings: Mexican oregano (Lippia berlandieri, L. graveolens), saffron (Crocus sativus), Mexican tarragon (Tagetes lucida), papaloquelite (Porophyllum ruderale) Sierra Madre oregano (Poliomentha madrensis), lavandin (Lavendula intermedia), Greek oregano (Origanum vulgare), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), and lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus).

Dwarf or drastically pruned trees with high-value fruit: dwarf varieties of figs (Ficus spp.), pomegranates (Punica granatum), cherries, including the Mahaleb cherry (Prunus mahaleb), olive (Olea europea), Sechuan peppers (Zanthoxylum armatum, Z. bungeanum, and Z. simulans), and Mediterranean sumac (Rhus coriaria).

Long-season annual herbs or perennial pharmafoods (nutriceuticals) that can tolerate frequent cuttings: sweetleaf stevia (Stevia rebaudiana), holy basil or tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum), damiana (Turnera diffusa), saffron (Crocus sativus), wild Lebanese cucumber-melon (Cucumis melo, a parent of the popular beit-alpha greenhouse cucumber); and chia (Salvia hispanica).

It is important to consider what horticultural design and density qualifies as having the optimal features required to grow in agrivoltaics conditions, for none of these proposed crops need to be grown in evenly spaced monoculture. For instance, the least sun-sensitive crop varieties can go on the periphery of the solar panels, preserving the core area for the most shade-tolerant varieties or species.

A Speaker Discusses Agrivoltaics in Arizona. Photo: AgriSolar Clearinghouse

Alternatively, taller woody perennials can be placed under the highest levels of the panels, with the shorter varieties or species reserved for the shortest area toward the “front” of the angled panel. However, new designs of photovoltaics have computerized solar trackers for mobile or reclinable units, so that may become an irrelevant consideration in the future. Another option is to grow indeterminate vine crops such as cucumbers or grapes on the periphery of the solar panel shadow. This might allow those crops to “crawl out,” and provide greenery that reduces ambient temperatures on the panel surface. This may increase daily energy production efficiency and extend the lifetime of the panel(s).

A final consideration is that for extremely high-value crops like pharmafoods and pharmaceuticals, screening the sides of the growing space may reduce or halt predation by insects or vertebrate herbivores. The overall cost of construction and production in an agrivoltaic system would remain far less than that for most commercial greenhouses, but the agrivoltaic micro-climate and growing space would then be considered a “controlled environment.”

When selecting crops that are uniquely suited to be grown in agrivoltaic settings, consider the guidance provided above. Ask questions related to the features of the solar panel design, including height, width, and other design features, as well as measurements. Then, consider the plant characteristics that are being considered for that site: height, width, water consumption, root depth, harvesting schedule, etc. Next, form a strategy from the characteristics you have identified for both the panels and the plants and make an informed decision about what will work best for that specific agrivoltaic site, as agrivoltaics conditions can vary from one site to another.