By Lindsay Mouw, Center for Rural Affairs

What’s the latest buzz about solar energy? It’s likely the thousands of honey bees that call solar fields home.

Commonly referred to as “agrisolar beekeeping,” the practice of placing beehives on or near solar fields is a burgeoning industry. While photovoltaic panels are generating energy from the sun, bees are busy at work making honey and pollinating the native and non-invasive plant species below the panels.

This business model creates a multi-stacking of benefits by using the land for multiple purposes simultaneously. When solar panel fields are planted with native and non-invasive plant species, not only is that land generating carbon-free energy, but also providing critical habitat for bees, monarch butterflies, and other insects, birds, and animals. It also creates new economic opportunities for local beekeepers and for the community in the form of energy generation tax payments.

As solar developers become aware of these benefits and strive to demonstrate responsible land stewardship, they are reaching out to beekeepers, such as Dustin Vanasse, CEO of Bare Honey based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, who may be interested in this practice. When a developer reaches out, Dustin says it is best that the two parties draft a contract that outlines expectations and responsibilities in order to establish a sound relationship with no surprises before moving forward with a project.

According to Vanasse, the most common practice is to place hives just outside the fence of the solar field for liability and insurance reasons. Therefore, the beekeeper will need to ensure there is enough right-of-way space for the hives and to maneuver any necessary equipment. The responsibility of managing the pollinator species should be outlined in the contract as well but is typically the responsibility of a vegetation management service contracted with the project developer.

Vanasse also noted that it is helpful to obtain the seed mix of the site and management calendar from the developer to inform handling of the bee colonies. To meet pollinator goals, a vegetation management calendar should accommodate bloom seasons to ensure the bees have access to the diversity of species at the site.

Joel Fassbinder, a solar beekeeper in Decorah, Iowa, and owner of Highlandville Honey Farm, suggests waiting to place hives on agrisolar locations until the second or third year after the groundcover has been seeded to allow time for the seed to take hold and develop bountiful flowers.

“I also register my bees on Field Watch, a tool that communicates between beekeepers and pesticide applicators,” Fassbinder said.

Solar beekeepers are seeing an increasing opportunity in the market for their solar-grown honey products.

“Anymore, customers want more than just a good tasting product, they also want to support environmental work,” Vanasse said.

However, as the demand for environmentally responsible products has grown, so has the concern of greenwashing tactics employed by companies that make green claims or use misleading marketing and labeling without actually taking meaningful steps to generate a sustainable or environmentally responsible product. Vanasse said transparency in their operations is key. He frequently brings people out to his agrisolar beekeeping sites so they can see the multi-use purposes of the facilities and provides education services about the industry to project developers, county elected officials, schools, and beekeeper groups.

Vanasse noted that the state of Minnesota requires all ground-mounted installations to complete a solar pollinator scorecard during the planning stage and after the establishment period of three years. This scorecard ensures the quality of pollinator habitat at the site is reported to the Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources. The scorecard is part of Minnesota’s Habitat Friendly Solar Program, a result of state policy that requires verification of adhering to the standards set by the Board of Water and Soil Resources.

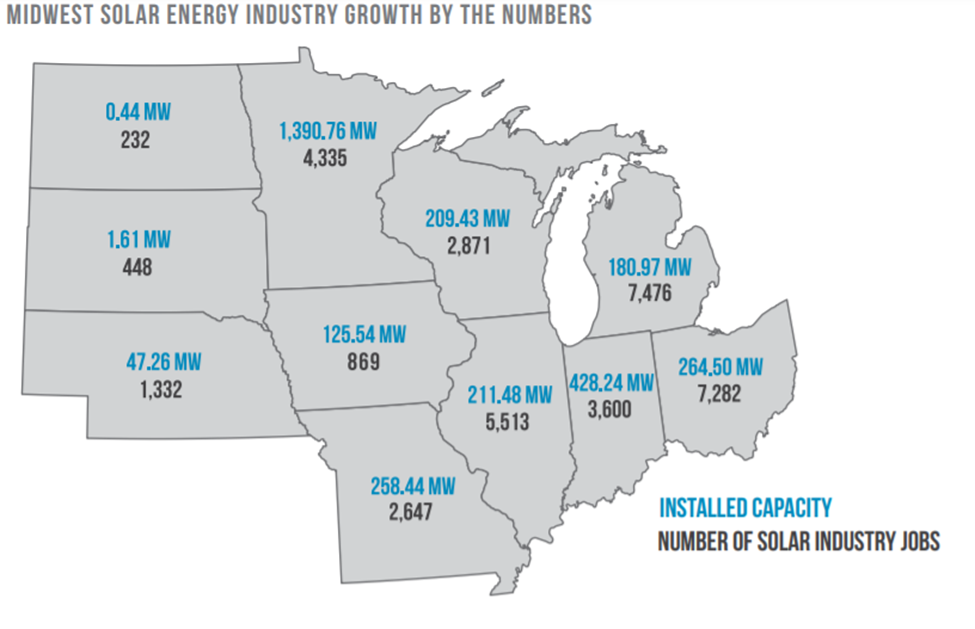

Planting solar sites with pollinator species is quickly becoming the norm, in part because of policies like those in Minnesota and New York. In 2018, New York passed a bill that established a vegetation standard for ground-mounted solar arrays. Such policies are promoting numerous environmental benefits and new opportunities for beekeepers.

“Consistently our best performing hives are located on the agrisolar pollinator sites,” Vanasse said. “These hives have a more diverse source of pollen as opposed to a monocrop site; the abundance and diversity of plants lead to a more balanced and diverse diet for the bees, making the hives stronger.”

Fassbinder agrees and says “overall agrisolar beekeeping has been a very positive experience.”

Nearby farmers also benefit from the hives through increased pollination of their crops, especially those that are pollinator-dependent, such as berries, apples, squash, and pumpkins. Researchers at Argonne National Laboratory found in a case study that there are 1.1 million hectares of land designated as proposed or potential solar sites in the U.S. The estimated value of pollinator habitats on the hectares of land that are suitable for pollinator habitat is between $1.5 billion and $3.2 billion.

For beekeepers interested in getting into the photovoltaic beekeeping industry, Vanasse and Fassbinder recommend reaching out to Bare Honey or the solar project developer, whose information is usually available on a fence sign surrounding the project.