New Study Shows Broccoli as Ideal Crop for AgriSolar Farms

According to a new study by researchers of South Korea’s Chonnam National University, broccoli has shown to be an ideal crop to be grown under solar panels.

“As per the study, the shade offered by the solar panels helps the broccoli get a deeper shade of green, which makes it look more appealing and it does so without a major loss of crop size or nutritional value. However, financial benefits for farmers producing solar energy are considerably more compared to the income generated by growing broccoli — nearly ten times more. Essentially, farmers are missing out on an opportunity by not having solar panels installed on the field.” – IT Technology

Cattle Graze Under Solar Panels in Minnesota

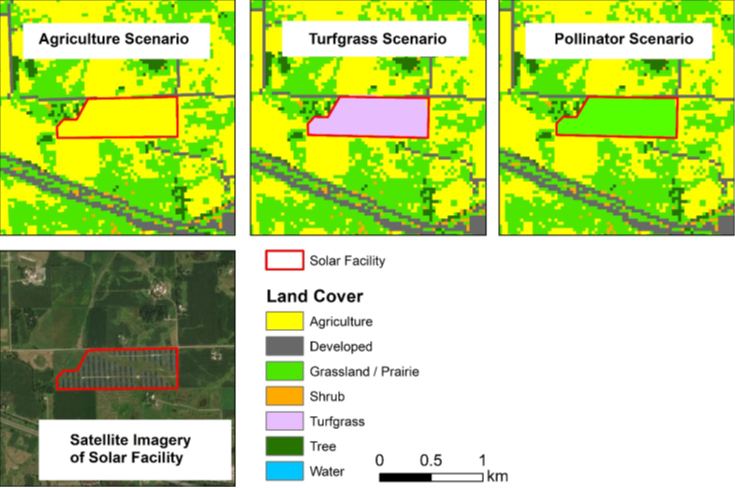

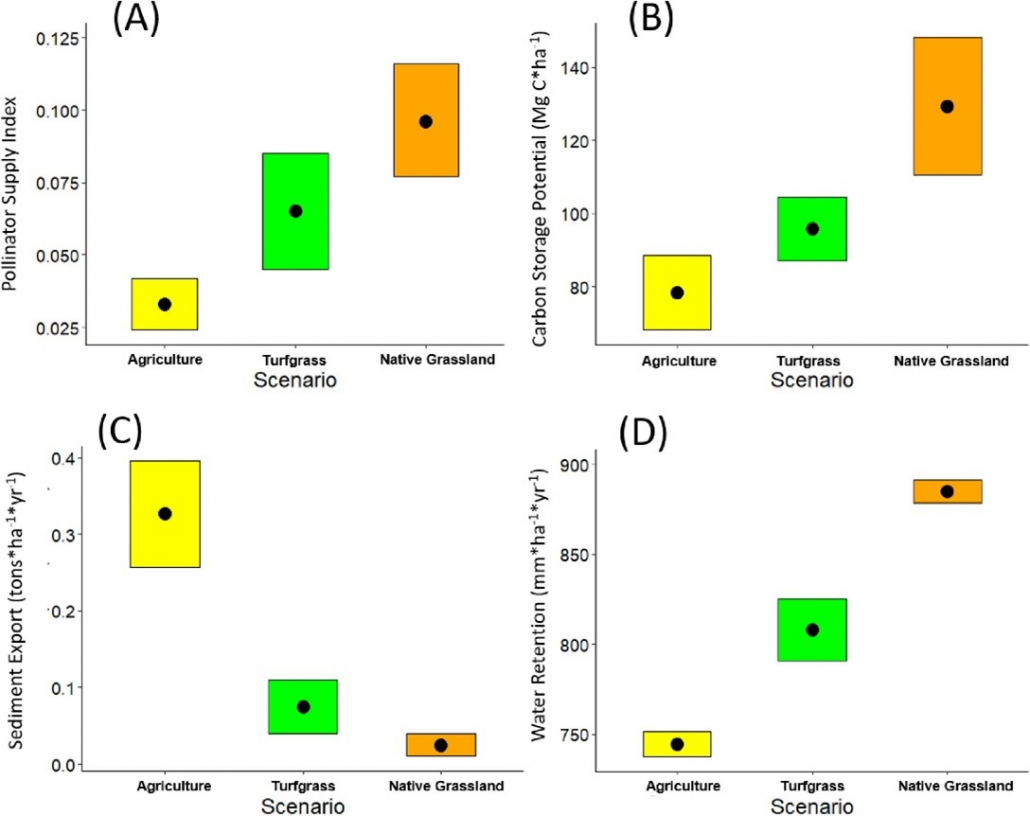

Cattle grazing under solar panels along U.S. Highway 59 in Morris, Minnesota, are under the direction of Bradley Heins, Ph.D., University of Minnesota. The cattle use the panels for shade and shelter, while other aspects of the operation are being studied further, such as water-runoff usage, pollinator habitat, and various potential crops to be grown.

“Studying both the theoretical and the practical applications of agrivoltaics is James McCall, a researcher in mechanical engineering with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). NREL is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy.

‘To achieve the current administration’s decarbonization goals, we are going to need 10.3 million acres of land (by 2050) to achieve a high decarbonization and electrification scenario,’ said McCall. ‘We see a lot of pushback from local communities who don’t really want these projects on their land or in their community, a solution that has popped up is agrivoltaics.’

It’s possible that agrivoltaics could help develop a more pastoral environment for communities, and additional revenue streams for developers and farmers.” – Farm Ranch Guide

U.S. Army Launches Floating Solar Farm

Last month, a ribbon cutting took place for a U.S. Army floating solar farm, sited on Big Muddy Lake at Camp Mackall on Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

“Fort Bragg is the largest military installation by population in the Army, with around 49,000 military personnel, 11,000 civilian employees, and 23,000 family members. The 1.1-megawatt (MW) floating solar farm includes 2 MW/2 megawatt-hour of battery energy storage.

The floating solar farm is a collaboration between Fort Bragg, utility Duke Energy, and Framingham, Massachusetts-based renewable energy company Ameresco. The U.S. Army’s announcement explains: This utility energy service contract project will provide carbon-free onsite generation, supplement power to the local grid, and provide backup power for Camp Mackall during electricity outages.

The U.S. Army has a goal of slashing its emissions 50% by 2030 and achieving net zero by 2050. It also wants to proactively consider the security implications of climate change in strategy, planning, acquisition, supply chain, and programming documents and processes.” – Electrek